Growing nitrogen in the forest garden

My favorite part of Creating

a Forest Garden was Crawford's simple numerical explanation of how

to create a closed loop garden with nitrogen-fixing

plants interspersed among your fruit trees. His rule of thumb

is to fill about 40% of your canopy with nitrogen fixers if your forest

garden is made up of high demand fruit trees (with lower percentages

possible if you're willing to truck in fertility or use lower-yielding,

less mainstream types of fruits). The nitrogen will make its way

from these trees, shrubs, and herbs to your fruit- and nut-producing

plants when the former lose their leaves, discard feeder roots, or hook

into the mycorrhizal network, and you can expedite nitrogen movement

by cutting branches and laying them underneath your high value plants

as a nutritive mulch.

My favorite part of Creating

a Forest Garden was Crawford's simple numerical explanation of how

to create a closed loop garden with nitrogen-fixing

plants interspersed among your fruit trees. His rule of thumb

is to fill about 40% of your canopy with nitrogen fixers if your forest

garden is made up of high demand fruit trees (with lower percentages

possible if you're willing to truck in fertility or use lower-yielding,

less mainstream types of fruits). The nitrogen will make its way

from these trees, shrubs, and herbs to your fruit- and nut-producing

plants when the former lose their leaves, discard feeder roots, or hook

into the mycorrhizal network, and you can expedite nitrogen movement

by cutting branches and laying them underneath your high value plants

as a nutritive mulch.

Let's do some fun nitrogen

math! First of all, you have to consider whether your

nitrogen-fixing plants are growing in full sun, partial shade, or full

shade --- the plants need full sun for peak nitrogen-fixing ability,

with the amount of nitrogen sucked out of the air declining linearly as

the plants are subjected to more and more shade. In full sun, an

average nitrogen fixer will make available 0.033 ounces of nitrogen per

square foot of canopy area, meaning that a hefty alder 16 feet in

diameter would fix about 6.6 ounces of nitrogen per year.

Let's do some fun nitrogen

math! First of all, you have to consider whether your

nitrogen-fixing plants are growing in full sun, partial shade, or full

shade --- the plants need full sun for peak nitrogen-fixing ability,

with the amount of nitrogen sucked out of the air declining linearly as

the plants are subjected to more and more shade. In full sun, an

average nitrogen fixer will make available 0.033 ounces of nitrogen per

square foot of canopy area, meaning that a hefty alder 16 feet in

diameter would fix about 6.6 ounces of nitrogen per year.

Meanwhile, heavy feeders

(including apples, peaches, and most of the mainstream fruit trees)

need about 0.026 ounces of nitrogen per square foot of canopy. So

a semi-dwarf apple tree with a canopy spread of 15 feet would need

about 4.6 ounces of nitrogen per year. It's easy to see how

planting one nitrogen-fixing shrub (like the alder detailed above) per

fruit tree could do the trick.

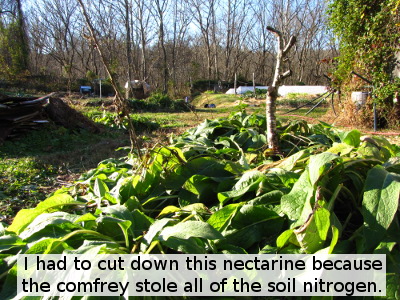

Crawford included numbers on

alternative source of nitrogen too, such as 0.18 ounces of nitrogen per

cutting for one comfrey plant, 0.20 ounces of nitrogen from each peeing episode, and 0.096 ounces of

nitrogen per pound of manure applied. I'm a bit disappointed that

he didn't make the distinction that comfrey is not a nitrogen-fixer, though,

and that although you can cycle nitrogen with its leaves, the

plant has a tendency to suck that nitrogen right back up in poor soil. On the other hand, if

you plant comfrey beyond the eventual canopy spread of your fruit

trees, fertilize the comfrey with urine, and cut leaves regularly, the

dynamic accumulator could provide quite a bit of nitrogen and organic

matter for your fruit trees.

Crawford included numbers on

alternative source of nitrogen too, such as 0.18 ounces of nitrogen per

cutting for one comfrey plant, 0.20 ounces of nitrogen from each peeing episode, and 0.096 ounces of

nitrogen per pound of manure applied. I'm a bit disappointed that

he didn't make the distinction that comfrey is not a nitrogen-fixer, though,

and that although you can cycle nitrogen with its leaves, the

plant has a tendency to suck that nitrogen right back up in poor soil. On the other hand, if

you plant comfrey beyond the eventual canopy spread of your fruit

trees, fertilize the comfrey with urine, and cut leaves regularly, the

dynamic accumulator could provide quite a bit of nitrogen and organic

matter for your fruit trees.

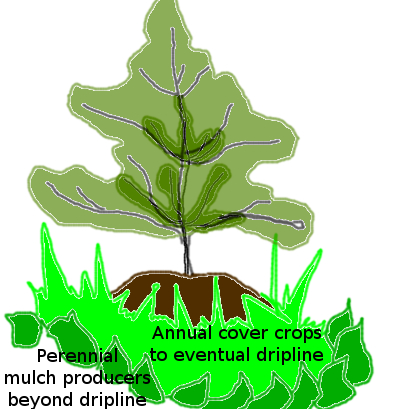

My other complaint with the

fertility section of the book is that it doesn't consider mulch, which

seems to be a much more time-consuming trucked-in component during the

establishment stages of a forest garden than nitrogen is. (If you

include

animals in your forest gardening system, nitrogen is pretty easy to

come by.) I suspect that this lack is due to Crawford gardening

on high quality soil where he can begin to use herbaceous plants to

keep weeds at bay under trees within just a couple of years --- in the

sad soil of my forest garden, I'm not so sure I'll ever be able to

plant inside the dripline without negatively impacting my trees.

Instead, I'm considering planting chop 'n

drop plants between

the eventual canopies of the fruit trees for building organic matter.

My other complaint with the

fertility section of the book is that it doesn't consider mulch, which

seems to be a much more time-consuming trucked-in component during the

establishment stages of a forest garden than nitrogen is. (If you

include

animals in your forest gardening system, nitrogen is pretty easy to

come by.) I suspect that this lack is due to Crawford gardening

on high quality soil where he can begin to use herbaceous plants to

keep weeds at bay under trees within just a couple of years --- in the

sad soil of my forest garden, I'm not so sure I'll ever be able to

plant inside the dripline without negatively impacting my trees.

Instead, I'm considering planting chop 'n

drop plants between

the eventual canopies of the fruit trees for building organic matter.

Any handy rules of thumb

out there on what percent of the growing area should be devoted to chop

'n drop mulch producing plants? I'm also still taking suggestions

for top perennial species, even though I'm focusing on annual cover

crops at the moment.

| This post is part of our Creating a Forest Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

[1] (4.6 oz per year / 0.2 oz per pee) = 23 pees per year = about 1x every 2 weeks

And of course, many people say that pee repels deer, which might keep them from nibbling little leaves.

Incidentally, in Charles Frazier's book "Thirteen Moons," he describes an old Indian's apple trees as having huge apples, "like the apples in dreams" because he planted them over his old outhouse sites. Maybe that's a good alternative for vegetarians who don't want to keep / eat chickens.)

(Frazier's book is worth a read, by the way, if you live in the Appalachians. The audio book was very good. Not much about farming, but it gives a strong sense of what the place might have been like in the frontier days.)

N content of various plants: http://www.helpguide.org/life/organic_foods_pesticides_gmo.htm

Only N fixing bacteria actually add N to the soil, using atm. N2 as the outside source, so only the legumes actually build the soil around themselves. Non-legume Chop & Drop plants would merely take up soil N, use it, then return it as they decay: no net change unless grown elsewhere & carried in....Using manure as a N source also works by transporting the N from the pasture, depleting it there, to your garden. The pasture needs to contain legumes to be sustainable.

Your figures for "one pee supplying the N for a year's tree growth" doesn't sound right. Plants are 2-5% N according to the site above, so every 1 lb of foilage would contain ~ 0.5-0.8oz of N. and we won't even mention the inefficiencies of converting the urea to nitrates. But still, why waste the pee?

Faith --- Thanks for the book recommendation! I tried to get into Cold Mountain, but as I recall there was too much war for my tastes. Hopefully this one will be more up my alley!

Doc --- That's the exact point I was getting at when I wrote "I'm a bit disappointed that he didn't make the distinction that comfrey is not a nitrogen-fixer, though, and that although you can cycle nitrogen with its leaves, the plant has a tendency to suck that nitrogen right back up in poor soil." However, what you may not realize (I didn't until I started reading my first forest gardening book) is that legumes aren't the only nitrogen-fixing plants. Alders, autumn-olives, and other actinorhizal plants also fix nitrogen.

To be honest, I haven't checked his math with the trees, but I only use half to one five gallon bucket of composted manure on each fruit tree each year, so it sounds about right. Of course, it would be better for the earth if people used rotational grazing and kept all the manure on the pastures, but when you milk cows or stable horses inside in preparation for riding them, the manure builds up and ends up being a waste in today's society. So I'm glad to turn that waste into my garden fertility.

RE: peeing on trees-- there's one good horticultural use for my son even before he learns how to selectively weed. He loves peeing outside. Maybe I can train him to look for the plants with yellowing leaves.

I don't know about the chop and drop question.I'm curious now, though.