The Jean Pain Method

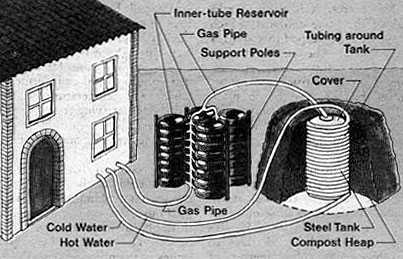

We dream of someday leaving the mainstream

electricity grid behind and becoming energy independent. Although

solar panels or hydropower have been top of our list in the past, Jerry clued me in to the Jean

Pain method --- a technique of converting wood chips into methane,

heat, and compost. We're nowhere near taking the plunge to that

level of production, but maybe it would be a loftier goal than saving

our pennies for solar panels?

We dream of someday leaving the mainstream

electricity grid behind and becoming energy independent. Although

solar panels or hydropower have been top of our list in the past, Jerry clued me in to the Jean

Pain method --- a technique of converting wood chips into methane,

heat, and compost. We're nowhere near taking the plunge to that

level of production, but maybe it would be a loftier goal than saving

our pennies for solar panels?

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

First, article you point to is from Reader's Digest, which is not the most tech savvy publication around, to put it mildly. I remember an article of theirs about faired recumbents (the vector, if memory serves), which was way too optimistic about the speed that an average cyclist would be able to reach in such a machine.

Second, the talk page on appropapedia about the Jean Pain article has several commenters questioning the amount of gas produced &c, and with good reason.

As you can see from a articles about anearobic digestion, a simplified reaction equation of the process creates methane and CO₂ in equal amounts of molecules. In practice biogas will contain 25-50% CO₂. So your gas burner or engine will not produce as much heat on a given flow of biogas compared to a equal flow of pure methane. Unless you filter out the CO₂ (which is presumable what the "washed through small stones in water" is about).

Unless you want a huge low-pressure gas storage balloon (imagine that being struck by lightning ), you'd want to "wash" most of the CO₂ from the biogas and then compress it. You also have to take into account the amount of work needed to create the several cubic yards fo wood chips nessecary for one batch!

), you'd want to "wash" most of the CO₂ from the biogas and then compress it. You also have to take into account the amount of work needed to create the several cubic yards fo wood chips nessecary for one batch!

Biogas can also contain hydrogen sulfide (rotten eggs smell) and volatile siloxanes which can deposit SiO₂ in burners and engines. (In large installations FeCl₂ is added to prevent the formation of hydrogen sulfide.)

The sources I've found indicate that during peak production you can expect the volume of the reactor per day in methane. The production of gas is normally distributed, so the average will be significantly lower. And to get optimal gas production you need to control the temperature carefully, With a fluctuating outside temperature and essentially random removal of heat from the tank by the hot water system this seems hard to achieve. Keep in mind that you're essentially running a small chemical plant. If the tank gets too hot, the bacteria will die.

Also, the waste water from the reactor might need treatment before it is safe to release in the environment.

I saw a TV program about innovative techniques once. It was about a dairy farmer who collected the manure from his cows (when they were in the stables) which is then anearobically digested to produce methane which was used to generate electricity and heat for the farm. The solid residue was used as compost or extruded and moulded into biologically degradable flower pots for seedlings (you can put those plants in the soil directly in their pots and they will feed the plant.) The runoff water was treated and used as fertilizer as well for the grassy fields that feed the cows.

It seemed to me it was a smart use of resources. The farmer in question definitely thought it was worthwhile. But you probably need to be a bit of a tinkerer. He cobbled together most of his equipment from the look of it, to keep costs down.